When you think of your favorite character from literature, you can probably visualize them the same way you can visualize a person you’ve actually met.

You know the color of their hair, their facial expressions, maybe even their nervous tics.

How did the author give you that mental image?

Chances are, the answer has something to do with direct characterization—the way the author described the character in the narration.

So how can you write characters that are as vivid and memorable as the ones in your favorite books?

Read on to see ten examples of direct characterization in literature, along with all the tips you need to use this literary technique in your own writing.

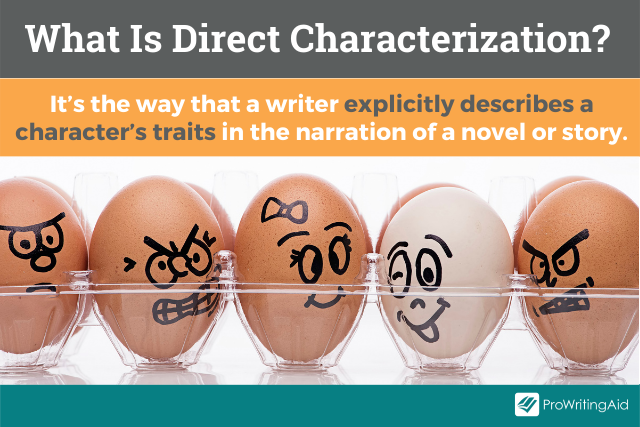

Direct characterization refers to the way a writer explicitly describes a character’s traits in the narration of a novel or story, e.g. He had green eyes or She was quick with a joke.

This technique is most often used the first time each character appears on the page, but small amounts of direct characterization can also be used continuously throughout the story.

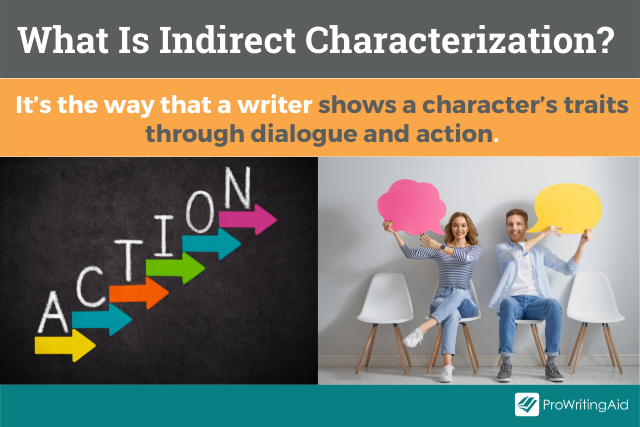

Direct characterization contrasts with indirect characterization, which refers to the way a writer shows a character’s traits through dialogue and action.

If you want to convey a character’s generosity with indirect characterization, for example, you might show the character lending money to a stranger in need.

If you want to convey a character’s bad temper with indirect characterization, you might show them slamming a door or shouting at their kids.

Here’s an example of what that might look like in writing:

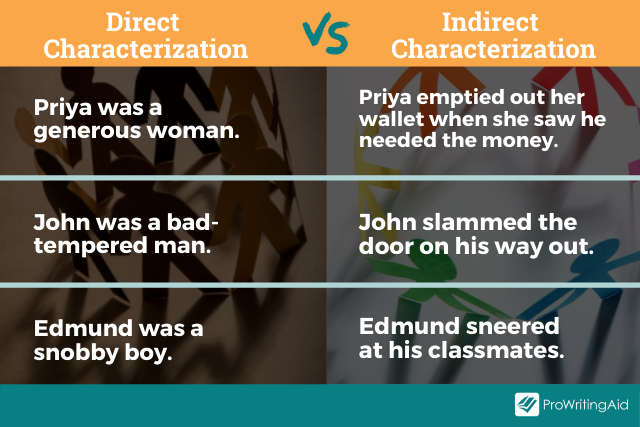

In the direct characterization example, the author explicitly states that Edmund is snobby.

In the indirect characterization example, the author shows Edmund’s snobbery through his actions and dialogue.

Both of these techniques are useful tools.

Use direct characterization for the most important aspects of character development, such as what the character looks like and what their personality is like.

Use indirect characterization to give the reader a deeper understanding of the character in a less straightforward manner as the story progresses.

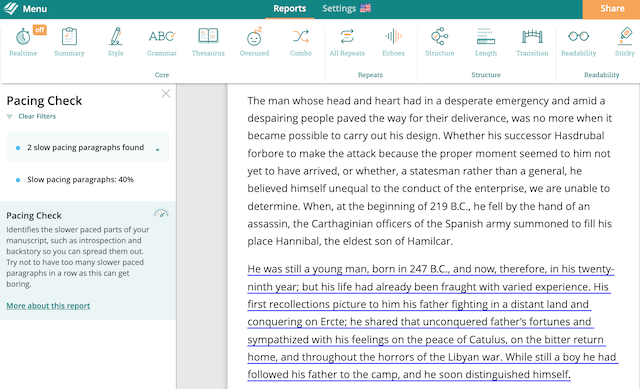

You can do this by balancing seemingly unimportant back narrative with the immediate action of your story.

ProWritingAid’s Pacing Report makes this process so much easier than going about it blind by giving you a visual representation of the overall pacing of your novel.

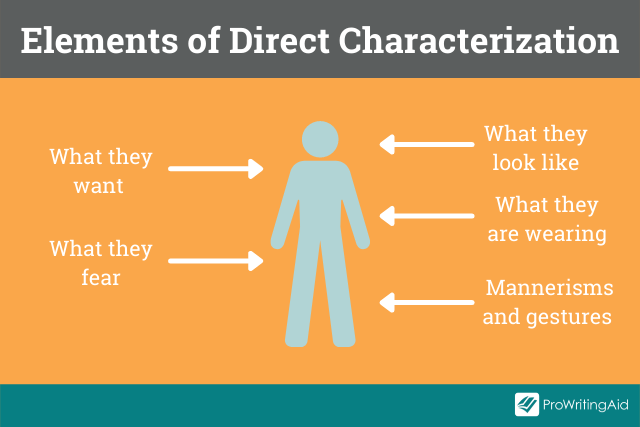

There are many details an author can include in direct characterization.

Direct characterization can include the character’s physical description, such as:

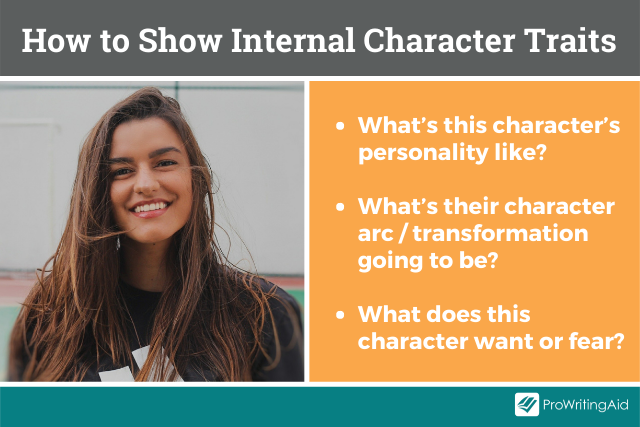

Direct characterization can also include the details of a character’s inner world, such as:

Let’s take a look at ten examples from literature.

Elodin was younger than the others by at least a dozen years. Clean-shaven with deep eyes. Medium height, medium build, there was nothing particularly striking about him, except for the way he sat at the table, one moment watching something intently, the next minute bored and letting his attention wander among the high beams of the ceiling above. He was almost like a child who had been forced to sit down with adults.

In this paragraph, Patrick Rothfuss introduces Elodin, the Master Namer at the University.

We see that Elodin both looks like a child ("younger than the others," "clean-shaven") and behaves like a child ("bored and letting his attention wander").

Rothfuss uses Elodin’s surprising appearance and mannerisms to convey his eccentric personality.

I am always honest about my capabilities. I am very pretty, though my prettiness lacks depth and therefore misses beauty by a hair. I have an extremely expressive face that I can contort at will. I am short, but I have a serviceable chest and practically perfect calves. For stage work I have a rich voice which carries well, though it is somewhat deeper than the fashion. I can alter it somewhat. I can pass for an American or a Frenchwoman, and I am working on a Muscovite lilt. Perhaps at twenty I shall be a superb dancer. Perhaps at thirty I shall be beautiful. Anything is possible.

This passage is an example of direct characterization in a first-person POV (point of view).

In spite of the first sentence of this paragraph, we have no way of knowing if the narrator is giving an honest assessment—we can only see her the way she sees herself.

We find out that she sees herself as pretty but not quite beautiful ("my prettiness lacks depth," "I am short," "I have a serviceable chest").

We also see that she’s confident she can adapt to the needs of the stage ("I have a rich voice which carries well. I can pass for an American or a Frenchwoman").

People had difficulty describing him. He was… he was “about.” He was about twenty, or about thirty. On Watch reports across the continent he was anywhere between, oh, about six feet two inches and five feet nine inches tall, hair all shades from mid-brown to blond, and his lack of distinguishing features included his entire face. He was about… average. What people remembered was the furniture, things like spectacles and mustaches, so he always carried a selection of both. They remembered names and mannerisms, too. He had hundreds of those.

Oh, and they remembered that they’d been richer before they met him.

This passage is Terry Pratchett’s description of Moist, an experienced conman and scammer.

Moist’s surface traits, which are described as average in every possible way ("His lack of distinguishing features included his entire face"), show the reader how well he’s perfected his profession ("They’d been richer before they met him").

This is a great example of a physical description that speaks to something deeper than the surface.

Bunny, for all his appearance of amiable, callous stability, was actually a wildly erratic character. There were any number of reasons for this, but primary among them was his complete inability to think about anything before he did it. He sailed through the world guided only by the dim lights of impulse and habit, confident that his course would throw up no obstacles so large that they could not be plowed over with sheer force of momentum.

In this passage, Donna Tartt describes Bunny’s personality.

We learn that he’s the type of person who makes decisions based on habit rather than forethought ("He sailed through the world guided only by the dim lights of impulse and habit").

Tartt also uses indirect characterization in other scenes of The Secret History to show us Bunny’s impulsivity, but this paragraph of direct characterization helps cement that personality trait in a more obvious way.

Wesley was tall, young and balding, smooth-featured as if rolled like a pebble, with a faint and meaningless expression of affability. He wore a three-piece suit of blue material. Scents of lime and mint came from Wesley’s mouth, cheeks and armpits. For the entire flight he had crossed his legs and smoked a pipe and answered Arkady’s questions with grunts. There was something awkward and milk-fed about Wesley, like a calf.

Martin Cruz Smith uses sight ("tall, young and balding," "smooth-featured," "three-piece suit of blue material"), sound ("answered Arkady’s questions with grunts"), and even smell ("scents of lime and mint") to describe Wesley, a CIA operative.

We get a comprehensive mental image of Wesley as an awkward and smooth-featured young man, which sets him apart from our pre-existing stereotypes of what a CIA operative might look like.

With Nath gone, Hannah followed Lydia like a puppy, scampering to her door each morning before Lydia’s clock radio had even gone off, her voice breathless, just short of a pant. Guess what? Lydia, guess what? It was never guessable and never important: it was raining; there were pancakes for breakfast; there was a blue jay in the spruce tree. Each day, all day, she trailed Lydia suggesting things they could do—We could play Life, we could watch the Friday Night Movie, we could make Jiffy Pop. All her life, Hannah had hovered at a distance from her brother and sister, and Lydia and Nath had tacitly tolerated their small, awkward moon. Now Lydia noticed a thousand little things about her sister: the way she twitched her nose once-twice, fast as a rabbit, when she was talking; the habit she had of standing on her toes, as if she had invisible high heels.

In this passage, Celeste Ng describes Hannah, the annoying but lovable little sister.

We see all the ways she begs her older sister Lydia for attention ("Guess what, Lydia? Guess what?"), following her around the house.

We also see Lydia beginning to notice her for the first time ("Now Lydia noticed a thousand little things about her sister"), since this paragraph is told from Lydia’s third-person perspective.

In the process, we learn something about both sisters and how their relationship is changing.

Bruno, my old faithful. I haven’t sufficiently described him. Is it enough to say he is indescribable? No. Better to try and fail than not to try at all. The soft down of your white hair lightly playing about your scalp like a half-blown dandelion. Many times, Bruno, I have been tempted to blow on your head and make a wish. Only a last scrap of decorum keeps me from it. Or perhaps I should begin with your height, which is very short. On a good day you barely reach my chest. Or shall I start with the eyeglasses you fished out of a box and claimed as your own, enormous round things that magnify your eyes so that your permanent response appears to be a 4.5 on the Richter? They’re women’s glasses, Bruno! I’ve never had the heart to tell you.

In this passage, we see us a physical description of Bruno, the narrator’s best friend, narrated in second person.

The traits he chooses to mention are unique and memorable ("your white hair lightly playing about your scalp," "the eyeglasses you fished out of a box").

They’re also interspersed with commentary from the narrator that make it clear how he feels about Bruno—a rare mix of affection and exasperation ("They’re women’s glasses, Bruno!").

Sybil’s face is heart-shaped, wide at the temples, with a small, emphatic chin. The truth is, it’s her father’s face. Distantly Finnish, midwestern, wide open and friendly. You can almost sense the ball fields and the Coca-Cola and the square dances that it took to produce that kind of a face.

In this passage, Amity Gaige describes Sybil’s physical appearance, drawing on cultural references ("ball fields," "Coca-Cola," "square dances").

Even though the description mostly focuses on Sybil’s face, we also get a clear sense of what Sybil’s personality is like.

But seven-year-old Werner seems to float. He is undersized and his ears stick out and he speaks with a high, sweet voice; the whiteness of his hair stops people in their tracks. Snowy, milky, chalky. A color that is the absence of color. Every morning he ties his shoes, packs newspaper inside his coat as insulation against the cold, and begins interrogating the world. He captures snowflakes, tadpoles, hibernating frogs; he coaxes bread from bakers with none to sell; he regularly appears in the kitchen with fresh milk for the babies. He makes things too: paper boxes, crude biplanes, toy boats with working rudders.

In this passage, Anthony Doerr introduces us to Werner, an unusual child with white hair and an extremely curious mind.

Though his physical traits are arresting, it’s Werner’s physical habits and mannerisms ("he captures snowflakes, tadpoles, hibernating frogs," "he makes things") that ultimately show us what kind of child he is.

He had expected her to be passably attractive, with the bloom of a young girl, but the face she shows when she draws back her veil is like a Madonna painted by a great master, beautiful and sad and wise. He can see her fair hair glinting under the cloth draped over her head, and the black clothes she wears enhance the elegance of her trim figure. She is certainly young, Orsino thinks, staring at her, but she is ripe like a peach. You would paint her as summer rather than spring, an orchid rather than a snowdrop, a queen rather than a princess, Juno rather than Diana.

In this passage, Jo Walton shows us this character using a variety of comparisons and similes ("a Madonna," "a peach," "an orchid," "a queen").

Through the mental associations we have with each of these comparisons, we get a sense of the character.

When used well, direct characterization can help you present a realistic and fully fleshed-out version of your characters.

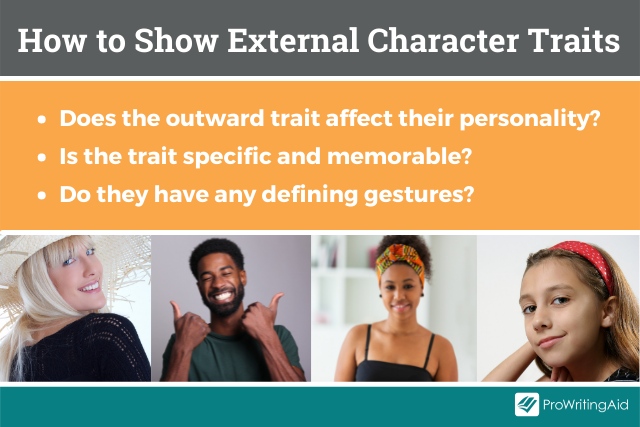

Here are some questions to ask yourself when you’re using direct characterization.

Showing a character’s physical description is especially necessary the first time we meet a new character.

Get as specific as you can. If your character is wearing a dress, tell us what kind of dress. If your character has red hair, tell us what shade of red.

Direct characterization is especially important for information relevant to the character’s motivation or growth.

If the story is narrated by another character, then all instances of direct characterization should reflect how that character thinks.

For example, the way Cinderella’s stepsisters describe Cinderella would be very different from the way Prince Charming describes Cinderella.

The former might sound envious and cruel, while the latter might sound admiring and romantic.

You can, in a sense, describe two characters at once by letting the narrator’s voice color their description.

Say you’re trying to use direct characterization to describe a character’s intelligence.

If this character’s intelligence makes the narrator feel inferior, you can describe their intelligence in a negative way ("She was a nerdy weirdo").

If this character’s intelligence makes the narrator feel awed, you can describe their intelligence in a positive way ("She was a brilliant scientist").

Doing so will tell you not just that this character is intelligent, but also how the narrator sees themselves in relation to this character’s intelligence.

Those are some of our favorite tips for using direct characterization in fiction writing.

What are your favorite ways to describe your characters? Let us know in the comments.

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.